The Thought: Are the constitutional rights of all citizens sacrosanct? Are they universal; are they consistently applied to peoples of various ethnicities?

Description: This lesson will give students an opportunity to explore the notion of citizenship and the rights afforded by the Constitution. Students will engage in dialogue about the various challenges to the incarceration argued in the Supreme Court, and the choices posed to and made by Nisei in the camps. We encourage discussions on the impact of these events on community cohesion.

Student Objectives:

1. Analyze the effects of the Loyalty Questionnaire on Japanese-American individuals and communities.

2. Identify various reasons why Japanese-Americans joined the military or chose not to, and the effects of their service on public perception of Japanese-Americans.

3. Explain how Japanese-Americans used the judicial system to challenge their incarceration.

Timeframe: Each activity is designed to last 30-45 minutes.

Materials: Loyalty Questionnaire Handout, Going for Honor, Going for Broke: The 442 Story (DVD), Worksheet 5.1, Bill of Rights

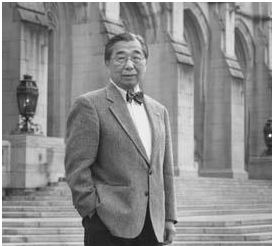

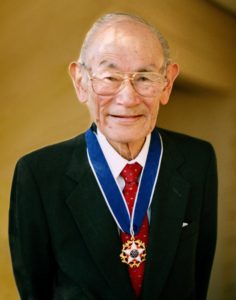

Readings: 45 Years Later, An Apology From The U.S. Government (Gordon Hirabayashi), About Fred Korematsu, Minoru Yasui 1916-1986, Ex parte Endo

Vocabulary:

draft

habeas corpus

legacy

loyalty

renounce

repatriation

sacrosanct

self-evident

unalienable

Additional Resources: Divided Destiny: A History of Japanese Americans in Seattle by David A. Takami, “Fifty Years Later: No No Boys Still Ask Why?”, “Japanese American Heroes and Citizens: You Decide” pamphlet, Japanese American Citizens League Fact Sheet, No-No Boy by John Okada, Japanese American Responses to Incarceration (video), Before They Were Heroes: Sus Ito’s World War II Images (exhibition)

Teacher Preparation: Read pg. 66-78 of Divided Destiny: A History of Japanese Americans in Seattle. Review the information in the Japanese American Citizens League Fact Sheet and Japanese American Heroes and Citizens: You Decide pamphlet.

The activities in this section are geared for grade 7 and up. Teacher discretion is encouraged in developing differentiated activities for younger students.

Activity 1: Loyalty Questionnaire

1. Tell students that although Japanese-Americans were incarcerated, the U.S. government still wanted to assess their loyalty to the United States, and distributed what became known as the loyalty questionnaire. The most controversial questions were 27, which asked if Japanese-American men would be willing to serve in the military (for women, the question asked if they would be willing to serve the war effort in other ways); and 28, which asked if they swore allegiance to the United States and renounced allegiance to the Japanese emperor. Discuss the trap of these questions; Japanese-Americans were incarcerated, yet asked to fight on behalf of the country who imprisoned them. In addition, Japanese immigrants were not allowed to become U.S. citizens, so answering “yes” to question 28 would leave them without any citizenship. The question also implies that Japanese-Americans were loyal to the Japanese emperor. Many Japanese-Americans resented being forced to prove their loyalty. [Pages 66-68 of Divided Destiny provide further background on the loyalty questionnaire.]

2. Have students read the questions on the Loyalty Questionnaire Handout. Ask students to brainstorm factors that might influence how someone chooses to respond. Possible factors include wanting to stay with family, anger at living conditions in the camps, a desire to prove their loyalty, or a need to preserve personal dignity.

3. Ask students to place themselves in the shoes of a Japanese-American in an incarceration camp and decide how they would answer the two questions, considering the factors they listed above. Designate one section of the classroom as the “Yes” corner and another as the “No” corner. Read Question 27 out loud and direct students to answer the question by moving to the appropriate corner. Remind students that they must answer “Yes” or “No”; giving a different answer or refusing to answer is not an option.

4. Ask students in each corner to share the reasons for their answer with each other. Then direct “Yes” students to find a “No” classmate and discuss their answers. Invite a few students to explain their partner’s answers to the class.

5. Repeat the activity with Question 28. After discussing their answers with classmates, ask students to reflect on why people chose to answer Yes or No. After hearing their classmate’s perspectives, would they change their answers?

6. Ask students what they think happened to Japanese-Americans who answered “no-no”. Most were sent to Tule Lake camp in California, designated as the “segregation center”. Others were repatriated back to Japan, and many U.S. citizens were pressured to renounce their citizenship. The loyalty questionnaire also caused many divisions among Japanese-Americans by categorizing them as “loyal” or “disloyal” and pitting those who answered “yes” against those who answered “no”. These divisions still affect Japanese-Americans today.

Extension: Have students write a persuasive essay arguing for answering “yes” or “no” to the loyalty questionnaire. They should include specific reasons and evidence to support their answers. Students may also wish to read the article “Fifty Years Later: No No Boys Still Ask Why?”, about one man’s experiences answering the loyalty questionnaire.

Activity 2: Going for Honor, Going for Broke

1. Tell students that starting in February 1943, Nisei men

who answered “yes-yes” to the loyalty questionnaire were allowed to join the United States Army, but could only serve in a segregated unit with other Japanese-American soldiers. Divide students into two groups; have one group brainstorm reasons why the U.S. Army decided to accept Japanese-Americans, even though they had been considered disloyal and forcibly removed from the West Coast. Have the second group brainstorm reasons why Japanese-Americans might join the military, considering they were being held in incarceration camps. Have both groups share their answers with the class. [The pamphlet Japanese American Heroes and Citizens: You Decide provides further background on Japanese-Americans in the military.]

2. Tell students that starting in 1944, Japanese-American men were subject to the draft. Many men who had not volunteered were required to serve in the military. About 300 Japanese-Americans resisted the draft and were sent to prison for the duration of the war. Ask students to reflect on how they would respond to being drafted. Would you agree to serve in the military, or resist and be sent to prison? Why would you make that choice? Discuss answers in small groups or as a class.

.

Activity 3: Constitutional Rights and Court Cases

1. Pass out the Bill of Rights and ask students to identify which rights were violated by incarcerating Japanese-Americans. Page 2 of the Japanese American Citizens League Fact Sheet provides more details on the violation of constitutional rights.

2. Tell students that Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, Minoru Yasui, and Mitsuye Endo all reacted to their rights being violated by turning to the judicial system. Divide students into four equal groups and assign one court case to each group. Give each group the appropriate article and ask them to work together to answer the following questions. (Students may also  choose to do additional research.)

choose to do additional research.)

a) What was this person’s background?

b) What government action was each person protesting?

c) What was this person’s motivation for protesting government actions?

d) Which constitutional rights were  violated in this case?

violated in this case?

e) What was the court’s decision?

f) What is the legacy of this court case?

3. Have each group make a 5-minute presentation to the rest of the class about their assigned individual and court case. As students listen to the presentations, ask them to make notes on similarities  and differences they see between the four cases, and what challenges and successes each individual had. Discuss their answers as a class.

and differences they see between the four cases, and what challenges and successes each individual had. Discuss their answers as a class.

4. Write the question “What can individuals do to protect constitutional rights for all?” on the board. Give students a few minutes to reflect on the question and write down their ideas, then ask each student to share one idea with the class. Collect their answers and post them in a corner of the classroom to refer back to in future lessons.