The Thought: Anti-Japanese racial hysteria drove national policy and popular opinion leading up to and during the Second World War. This hysteria helped the United States government to justify forcibly incarcerating American citizens of Japanese descent in concentration camps.

Description: Students will investigate the experiences of Japanese-Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor through analyzing historical documents, examining photographs, and expressing personal reflections.

Student Objectives:

1. Identify how ongoing anti-Japanese attitudes, stereotypes, and wartime hysteria led to the mass incarceration of people of Japanese descent following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

2. Explain how the United States government treated groups of people differently based on country of birth, ethnic background and geographic location during World War II.

3. Create personal connections between their own lives and experiences of Japanese-Americans after Pearl Harbor.

Timeframe: Each activity is designed to take approximately 30 minutes. We encourage teachers to choose which activities best fit their classes. Activities 1-5 are designed for all grade levels, while Activities 6-7 are appropriate for grades 7-9.

Materials: Yellow Terror Images [American Portrait #3, Japs Galore, Different Citizens, Housing Discrimination, Jap’s a Jap #5], Timeline of Wartime Events, Map of Exclusion Area, Photograph of Fumiko Hayashida, Tag Template, Terminology Handout, Worksheet 3.1

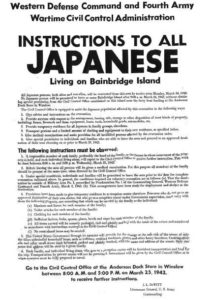

Readings: Journey to Topaz by Yoshiko Uchida (Chapter 1-5), “Instructions to All Japanese Living on Bainbridge Island”, Executive Order 9066

Vocabulary:

alien

Camp Harmony

discrimination

euphemism

evacuation

Exclusion Area

incarceration

internment camps

non-aliens

prejudice

relocation

stereotype

Additional Resources: Divided Destiny: A History of Japanese Americans in Seattle by David A. Takami (pg. 41-50), Japanese American Citizens League Fact Sheet, Fumiko Hayashida: The Woman Behind the Symbol (DVD), Power of Words Handbook by Mako Nakagawa and the National JACL Power of Words II Committee, Looking Like The Enemy (video)

Teacher Preparation: Read pg. 41-59 of Divided Destiny: A History of Japanese Americans in Seattle. Browse through the Power of Words Handbook to learn more about terminology used in this lesson.

Activity 1: Connecting the Present to the Past

1. Ask students how they think people of Japanese descent are generally portrayed in the media (movies, television, cartoons, advertisements, etc.), particularly their physical appearance. Are these images accurate? Why are they shown in this way? Explain that these images are examples of stereotypes (an oversimplified generalization about a particular group of people that does not change with new information).

2. Show students images of Roger Shimomura’s “Yellow Terror” exhibition. [Roger Shimomura is a Japanese-American artist born in Seattle. He spent several years in an incarceration camp as a child. For more information, visit his website.] In these images, people of Japanese descent are portrayed as having yellow skin, slanted eyes, and buck teeth. Many of them are also shown in military uniforms, showing their allegiance to the Japanese military. This was a very common stereotypical image in the United States before and during World War II. Ask students to reflect on the following questions and share their answers with the class.

a) How do you feel when you see these images?

b) If these were the only images you had seen of Japanese Americans, what opinions would you form about Japanese Americans?

c) Were these images accurate portrayals of Japanese-Americans? Are they stereotypes?

d) How did these images work to dehumanize Japanese-Americans?

e) How might these images have affected how other people in the United States felt and thought about Japanese-Americans?

3) Ask students to draw or write a more accurate portrayal of Japanese-Americans, based on information from previous lessons. Remind them there is more than one accurate portrayal, as each Japanese-American has different life experiences.

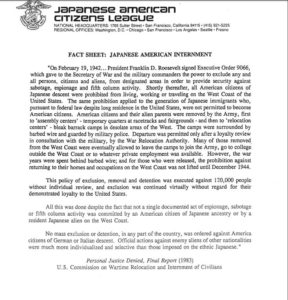

Activity 2: Timeline of Wartime Events

1. Pass out the timeline of events surrounding the United States entering World War II in 1941. Ask students how they think each event affected people of Japanese descent in the United States.

2. Remind students that although the United States was at war with Germany and Italy as well as Japan, the U.S. government did not incarcerate large numbers of German-Americans or Italian-Americans [approximately 11,000 German-Americans and 2,000 Italian-Americans were detained, in contrast to 110,000 Japanese-Americans]. Ask students why they think Japanese-Americans were treated differently, and discuss how anti-Japanese sentiment and racial stereotyping (discussed in the previous activity) contributed to their treatment.

3. Tell students that sixty percent of the people incarcerated were American citizens, born in the United States. Many of them had never been to Japan and/or could not speak Japanese. Ask students if they think it was acceptable to incarcerate American citizens without proof of crimes committed. [The legality of the government’s actions will be examined further in Lesson 5: Japanese-Americans and the Constitution.] Remind students that Japanese immigrants were prohibited from becoming American citizens; was it acceptable to incarcerate immigrants who likely would have become American citizens if permitted?

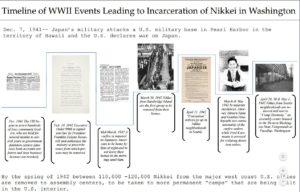

4. Show students the map of the Exclusion Area. The U.S. government removed all Japanese-Americans from this area and sent them to incarceration camps further inland. Ask students why Japanese-Americans from this region were incarcerated, but not Japanese-Americans living elsewhere. Point out that over 150,000 Japanese-American lived in Hawaii, but they were not incarcerated. Explain that the U.S. government claimed the Pacific Coast was a military target and that Japanese-Americans living there might be helping the Japanese army. These claims were never proven.

Activity 3: Seven Days to Pack

1. Have students read Chapters 1-5 of Journey to Topaz by Yoshiko Uchida. Discuss the experiences of Yuki, the main character. How does she react to having to leave her home and possessions?

2. Give students the following scenario:

The government has told your family that in one week, you will have to leave your home. You do not know where you are going, or how long you will be gone. You are only allowed to bring one suitcase for each person. What do you pack in your suitcase?

You must bring: clothing, toiletries, and other necessities.

You cannot bring: electronic devices, radios, binoculars, telescopes, weapons, scientific equipment, farming or gardening tools, religious items, animals.

3. Have each student make a list of what they will pack. If desired, pass out copies of “Instructions To All Japanese Living on Bainbridge Island” for students to read and guide them in their decision-making.

4. Have students share their list with a partner and see if the items on their lists are similar or different. Bring the class together and ask students to share one or two items from their lists. Ask students what was the hardest item to leave out? What items would you definitely bring?

5. Tell students they must now decide what to do with the items they cannot pack in their suitcase. They don’t know when or if they will be returning to their homes, so it is unsafe to leave items there. Brainstorm what they might do with these objects. For example, they could sell them, give them away, or try to store them somewhere. Ask students to think of the benefits and drawbacks of each option.

6. Remind students that they cannot bring animals with them. If you have pets or farm animals, what will you do with them?

7. Ask students to write down five words to describe how they feel in this situation, and share their answers with the class.

8. Tell students this activity is what Americans of Japanese descent faced in the spring of 1942. In addition to deciding what to do with their possessions, they also had to make arrangements for their businesses, farms, and houses. By this point, the U.S. government and FBI had arrested most of the Japanese community leaders; many families had to pack and prepare to leave without knowing where their husbands, fathers, or brothers were being held or if they would be reunited.

Activity 4: Photograph Analysis

1. Show students the photograph of Fumiko Hayashida holding her daughter Natalie. Ask them what they see in the picture. Where is she standing? What items is she holding? Where do you think she’s going? How do you think she is feeling?

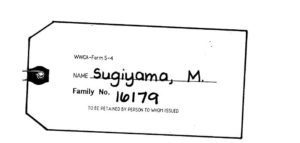

2. After students have analyzed the photograph, tell them that this is an image of Fumiko Hayashida, a Japanese-American woman from Bainbridge Island (she was also friends with Chiyo Murakami, featured in Lesson 2). This photo was taken on March 30, 1942, when all people of Japanese descent were removed from Bainbridge Island. Fumiko was photographed as she was waiting for a ferry to take her to Seattle, where the Bainbridge islanders were put on trains and taken to a camp in California. Fumiko was 31 years old at the time and had two children. Fumiko and her daughter are wearing tags with their family number written on them; each person was required to wear a tag to identify them.

3. Ask students how they think Fumiko felt as she waited for the ferry. Have them write a diary entry or poem expressing how they think Fumiko feels. Is she scared? What is she worried about? What will happen next?

Activity 5: Tags

1. Have students construct identification tags like the ones Fumiko and her daughter are wearing in the photograph from Activity 6. [tag-template Assign each student a number and write their name and number on each tag. Have the students attach the tag to their clothing and wear it for the rest of the day. (Alert other teachers if students will be wearing the tags to multiple classes). Ask students to keep notes on how many people comment on the tags and what questions they asked.

2. Use the information gathered to discuss what percentage of the school population knew about the Japanese-American incarceration and what kinds of questions they had. Were students surprised by reactions to the tags? What information did others know about Japanese-American incarceration?

3. Ask students how they felt while wearing the tags. Did they feel self-conscious or embarrassed? How did wearing a tag and having an assigned number change the way they viewed themselves or others? Did wearing a tag help them empathize more with Japanese-Americans?

Note: If it is not feasible to have students wear tags to other classes, have them attach the tag to their clothing and wear it while completing one of the other activities in this lesson. At the end of the class period, discuss the questions above as a class.

Activity 6: Euphemisms (Grades 7-9)

1. Introduce the concept of euphemism: mild or indirect terms used as substitutes for words or phrases considered offensive or harsh. Examples include “passed away” being used in place of “died” or “ladies’/men’s room” for “bathroom”. Ask students to brainstorm why people might use euphemisms.

2. Write this list of euphemisms on the board: evacuation, relocation, assembly center, internment, non-alien, relocation center. Ask students to write down what comes to mind as they hear each word.

3. Explain that these were terms used by the U.S. government to describe the experiences of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Ask students why they think the government used these terms. Discuss how using words such as “evacuation” and “relocation” made it sound like the government was protecting Japanese-Americans, and how using euphemisms made the idea of incarceration of Japanese-Americans more acceptable to the general public.

4. Divide students into pairs or small groups and ask them to think of more accurate words to use for each euphemism, based on what they have learned so far. Have them share their answers with the class.

5. Pass out the Terminology Handout, listing suggested terms to use in place of common euphemisms. Encourage students to use the suggested terms when discussing Japanese-American experiences.

Activity 7: Executive Order 9066 (Grades 7-9)

1. Pass out copies of Executive Order 9066. Focus the students’ attention on the second paragraph; ask them to read the paragraph silently and think about what groups of people this document referred to. Tell students not to worry about understanding each word, as the language can be rather difficult, but to focus on the general meaning of the paragraph.

2. Have students share their answers with the class. Tell them that although this Executive Order does not specify particular groups of people or places, it was aimed at Japanese-Americans on the West Coast.

3. Pass out Worksheet 3.1. Have students fill out the worksheet in pairs or small groups, analyzing the language used in the Executive Order. Ask them to share their answers with the class.

4. Divide students into small groups and have each group write down the meaning of Executive Order 9066 in their own words, referring to the worksheet if needed. Share with the class.

5. Discuss what affect the release of Executive Order 9066 had on the Japanese-American community. How did Japanese-Americans react to the news they might be removed from their homes? Encourage students to think about how they would feel if this document was aimed at them.

Extension Activity (Grades 6-9): Newspaper Research

Have students do research at the library or online to find newspaper articles from 1941-1945 talking about Japanese-Americans. Have them analyze the writer’s attitude; what words do they use when talking about Japanese-Americans? Is the writer sympathetic or not? What does the writer’s attitude say about public perceptions of Japanese-Americans?