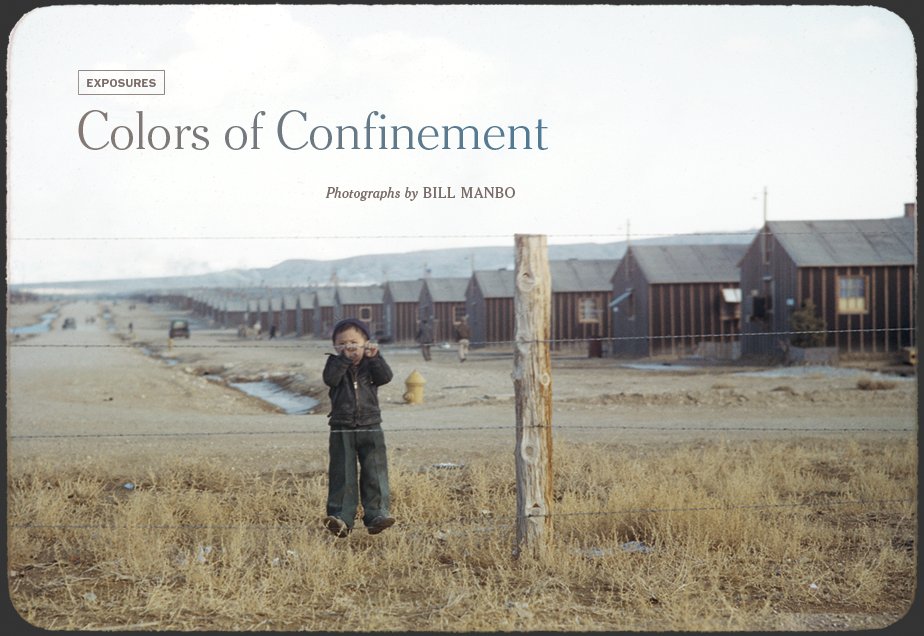

“In the photo, a young boy hangs on a fence. His face is partially obscured; his eyes hover just above his bent knuckles. His stance is playful. On first impression, he looks like any kid in the middle of play.

The background, however, tells another story. Receding endlessly into the horizon are the rows of barracks of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center, a World War II Japanese internment camp near Cody, Wyo.

During the three years it was open, August 1942 to November 1945, Heart Mountain held more than 14,000 people of Japanese ancestry. Many of them were American citizens. All of them — mechanics, farmers, green grocers, small children and grandparents — were forcibly removed from locations along the West Coast on unfounded (and patently hysterical) suspicions of espionage following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Among the detainees: Bill Manbo, an American citizen who, prior to being detained, had operated a garage in Hollywood. In addition to being a mechanic, Manbo was also a dedicated amateur photographer, shooting color at a time when the form was still nascent. (Kodachrome, the first widely used color film, had come on the market in 1935.)

In August 1942, thousands of Japanese Americans from Los Angeles began their lives as prisoners on a wide stretch of prairie in northwestern Wyoming. Among those forcibly relocated to Heart Mountain concentration camp was a photographer and auto mechanic from Hollywood named Bill Manbo, whose Kodachrome color photographs are the subject of the Japanese American National Museum’s Colors of Confinement.

Among the 18 photographs in the exhibition are rare documents that challenge the kind of imagery one might expect from internment camps. These images are not of dour-faced prisoners living in squalid conditions. Many of them feature scenes of a vibrant community taking part in activities like dancing, wrestling, and ice skating. A portrait of Manbo’s wife Mary and her family, dressed in formal attire, pieces together a semblance of normalcy.”

“When Japanese immigrants and Japanese-American citizens were torn from their daily lives and herded into internment camps with guard towers during World War II, they were told to only bring what they could carry. But they were also told what they could not carry. Among items initially banned by the U.S. Army’s Western Defense Command were bombs, ammunition, implements of war, codes or ciphers, explosives and the humble camera.

If anything, this is a testament to the incredible power of photography. Even one frame can change the tide of public opinion because photography has the power to add layers to our understanding of how events transpired and how people were affected.

The ban on cameras by the Western Defense Command was lifted in the spring of 1943. At that time, Bill Manbo’s 35mm Zeiss Contax became an outlet as well as a way of writing his family’s story at a time when even Japanese descendants born on American soil had their loyalty questioned.”

“They look like vacation photos at first glance. Women in flowery kimonos gossip together in a circle. A boy on ice skates takes his first steps on a crowded rink. Two sumo wrestlers share a chuckle in the ring as a crowd watches on.

But behind the smiles, the same shadowy presence looms in the background: the tar paper barracks that housed the thousands of Japanese-American prisoners of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming.

Bill Manbo, an auto mechanic from Riverside, Calif., took these photographs after he and his family were forced to move to a Japanese-American internment camp in 1942, just months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.”